The Catherinian Cycle in the world

Archdiocese Museum, Warsaw, Poland

University for Foreign Students, Siena, Italy

Salon of the Consulate of Italy, Grenoble, France

Galleria del Paiolo, Florence, Italy

Espace Oxalis, Avignon, France

Consulate of Italy - Columbus Centre, Toronto, Canada

Cal Poly State University Gallery, San Luis Obispo, USA

Italian Cultural Institute – Consulate-General of Italy, San Francisco, USA

Palazzo Piccolomini, Pienza, Italy

Cathedral of St. John The Divine, New York, USA

Church of San Martino, Chiusdino, Italy

European Parliament, Brussels, Belgium

Salon de l'Art, Plaisance du Touch, France

Waldorf Astoria Salon, London, England

Hall of the Rathaus, Wetzlar, Germany

Casa dei Carraresi, Treviso, Italy

Galleria San Vidal, Venice, Italy

Senate of the Republic, L’Orangerie, Paris, France

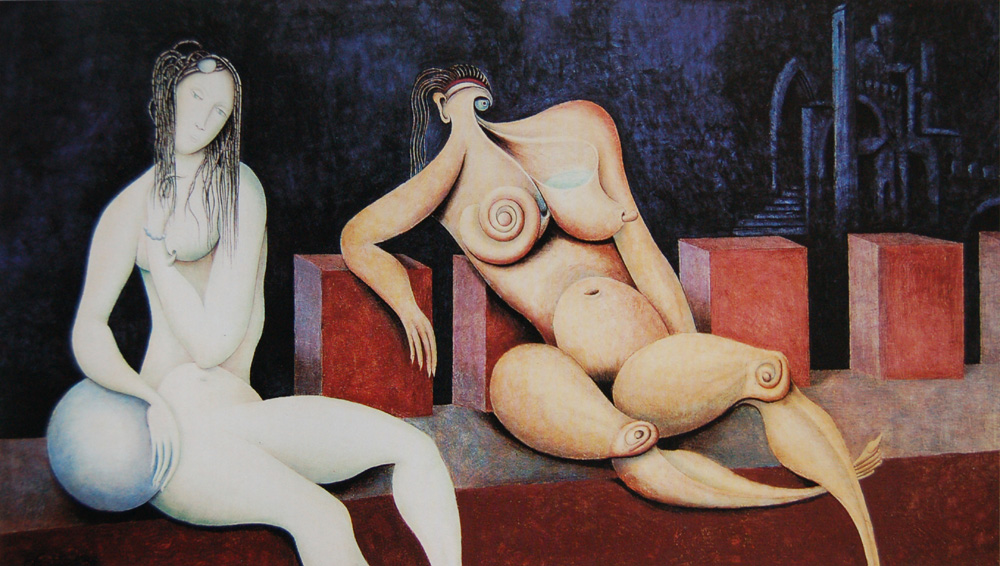

DIABOLICAL TEMPTATIONS

Nudity of the body

The dynamism and harmony of the figure reach their maximum expression by showing the body without garments that “... above all fulfils its primary function: to convey a message.” (1)

The dress is an unnecessary, inevitably figurative medium, the absence of which allows me to convey, through the naked body, a plurality of messages: all those I desire. The nudity of the Saint cancels any static effect. In other works the language of the body is taken to its extreme consequences for a game of graphic windings that cancel the external sign (contour) which is essentially confined to a marginal function. The subject thus treated acquires the maximum kinetic energy.

The conflict

On the left, Catherine’s white, surreal maidenly nakedness, barely touched by blurry “sfumato”. On the right a female figure to which I have imposed exasperated, exalted and “heated” forms and chromaticisms by the yellow background of beeswax. The result is a contrast of strong intensity and an immediately active reading.

The contrast of the two subjects is intended to emphasize the Catholic Church’s aversion to the human body and its sexuality (2).

The anatomy of the two women is functional to the primary action of the conflict and justifies its title.

Catherine

The Saint shows evident anatomical contradictions produced by two very distinct groups of elements that make up the following parts of the body:

Head– reclined as in 13th-century Madonnas to suggest abandonment and innocence in contrast with the lower part of the body.

Face– a delicate oval.

Hands– the fingers of the left hand run through the hair with a delicate gesture.

Sphere– symbol of perfection.

Breast– only one, bursting from the space between the two arms and discreetly protruding on the arm with a part of the nipple.

abdomen– its irregular shape and position break the harmony of the body.

Legs– not “virginal”.

Deformed woman

The woman of the “Temptation” is painted with full creative freedom.

Using a paint remover I am the hot air at the female figure. The wax heats up causing the paint to move over the surface. The female body undergoes a mutation showing itself in all its carnal disintegration. In the final phase I correct the colours and shapes that the deformation suggests to me. The complexion is warm due to the intense yellow of the beeswax.

Battlements

The battlements are specific Sienese architectural references. Their dimensions have been reduced to enhance the primary action of the figures. The missing blackbird at Catherine’s right side allows me to wrap them both up to the sphere with the dark shade of the sky. I could not apply the rules of perspective to the blackbirds because their thickness would have made them coarse and heavy.

Conclusions

No respect for anatomical proportions.

The soft hue of Catherine’s body, obtained by using white wax, unifies the formal elements that compose it. The colour of the sky is obtained by applying indigo, cobalt blue and black over emerald green and cerulean blue. Thus I was able to make the white background of the wax vibrate with greater intensity. The sitting position hardly attenuates the kinetic energy originated by the chromatic and formal contrast between the two women. All the colours seem animated. This is due to the irregular thickness of the underlying wax, which is also a source of chromatic intensity.

(1) Maria Caterina Jacobelli – “Una donna senza volto” - Ed. Borla

(2) Maria Caterina Jacobelli – “Il risus pascalis e il fondamento teologico del piacere sessuale” - Ed. Queriniana

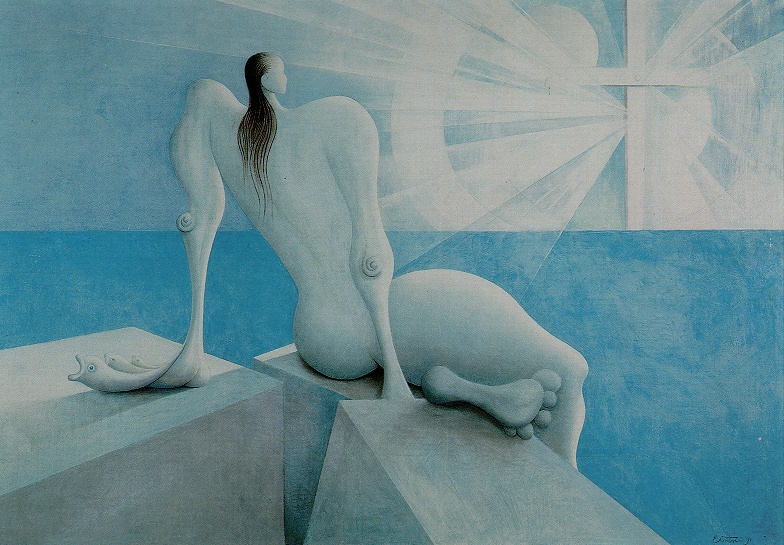

ECSTASY

Deep penetration of medieval spirituality. The city was immersed in nature, which pervaded everything. Silence, suspended in the air, breathed in by men, was humus of reflection, a stimulus for imagination.

Spirit of Nature and religious spirit–a hard distinction. Catherine’s mind and heart lived in this universe exalted by the woman’s religious intensity with her immense spiritual affliction.

The great attraction for this extraordinary female figure equals the difficulty of reading her letters.

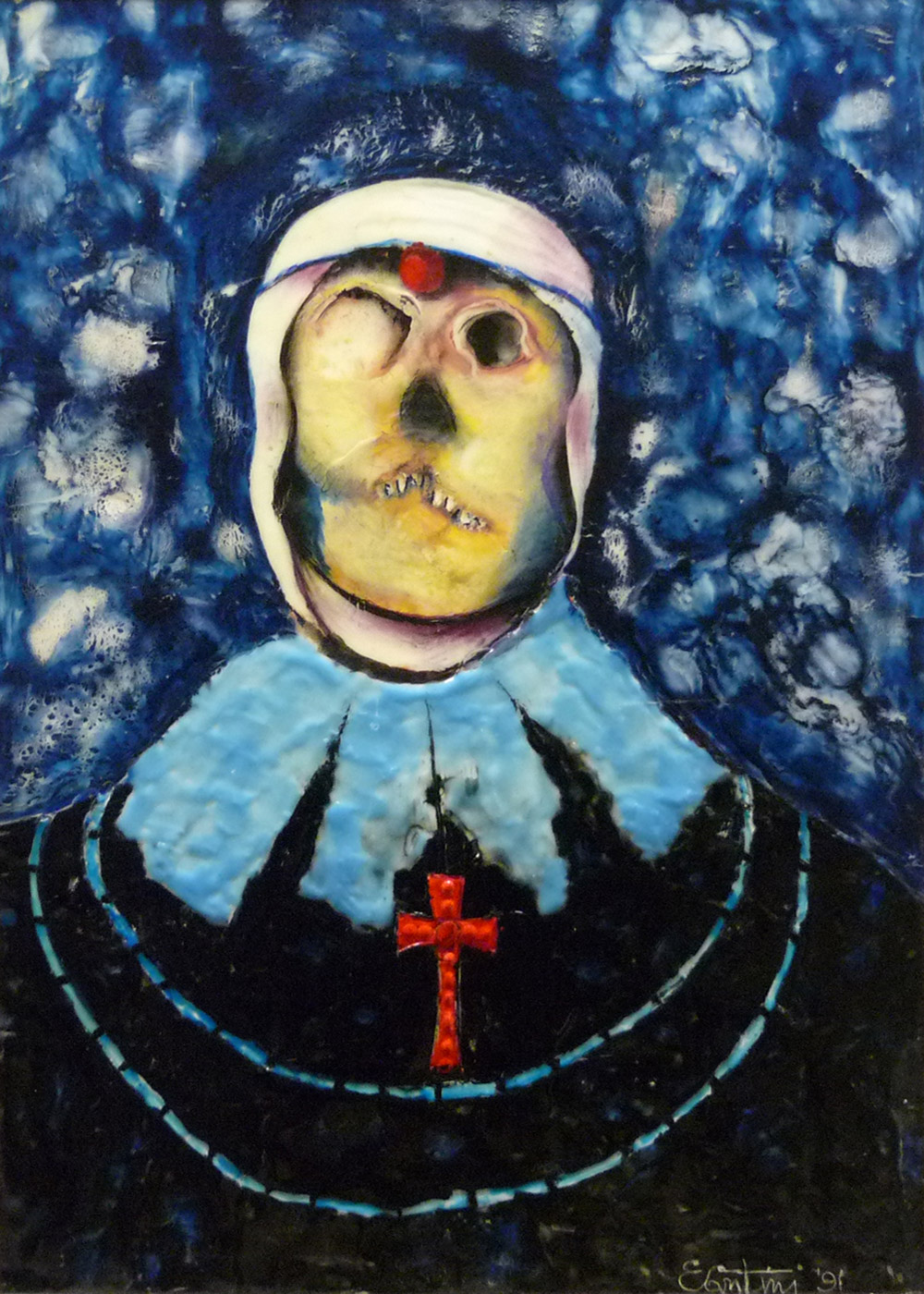

The memory of that vision of the relic, seen for the first time with the eyes of the child, materializes in the “Ecstasy”. A Proustian “intermittency” of the heart meant for those human remains kept in the Basilica of San Domenico. The “Ecstasy” is affected by that vision, which stimulates me to show the religious act with graphic deformations and exaggerated colours. The Catholic tradition describes the immobile woman in the ecstatic act but the strength unleashed within her contradicts the immobility of her body, which instead had to be prey to the dynamism impressed by the superhuman power penetrated into her depths. A very visible upheaval coinciding with the maximum intensity of the phenomenon. Her body could not withstand the tremendous tension caused by that strength. We can admit, if anything, that the action of this cosmic fluid had been so intense that it quickly weakened her energies, limiting the movement time of her slender body.

I had seen Gianfranco Mingozzi’s documentary movie “La Taranta” on a pagan-religious ritual held yearly in the Apulian town of Galatina. The feature film showed women dressed in a long white tunic dancing to the sound of some musical instruments. Their pace increased with time becoming apparently uncontrolled, then the dancers collapsed to the ground, with their night-dresses open, showing the naked bodies now possessed by some mysterious power plunged into them. That memory has influenced my painting since the initial phase. Until the 1960s this ritual incredibly took place in a Catholic chapel in Galatina.

“Ecstasy” is divided into two distinct parts: the lower part shows the action that justifies the title, the upper part the city. At the centre the walls that clearly separate the static and the dynamic parts of the composition. The walls and the landscape, however, do not play a complementary role either because the Saint belongs to Siena or because this space takes half of the picture.

Everything must be dramatic: the bandaged head opened by a slit in the centre of the forehead, the snake-like elements that originate there and spread on the surrounding ground immersed in carmine red, the breasts (“my” breasts!) bursting from the base of the neck of the horse with its curvilinear escape to the right. The animal’s head is stretched forward to emphasize the unbearable tension of the black neck while an unlikely mane, consisting of black horizontal lines stretched to the left, balances the dynamism of the neck that would otherwise drag the observer’s eye too much to the right.

Mnemonic fragments entered “Ecstasy”: the breasts, the leg, a modern shoe refer to the pagan rituals of our times. The graphic deformation of the head refers to the relic venerated in the church of San Domenico. Two reasons justify the presence of the horse: its formal harmony and the love for this animal so deeply rooted in the heart of our city.

The two columns that form a cross are symbols of stability. All the action of the ecstasy rests on these two elements. Their colour –a pale blue– made stronger when in contact with carmine red– tends to enhance the dynamism of the ecstasy. The cypress is also a symbol of immobility. Its harmony, unlike the columns, is the work of nature. The ascending shape of the two cypresses interrupts the roundness of the hill whose chromatic strength, made even more evident by the blue-violet of the sky above, would project it too far, beyond the walls. The verticality of the two trees also represents a psychological contact with the towers and other architectural elements of the city whose vertical monotony is broken both by a sphere and a dome, painted grey and genuine helium blue. Their colour contrasts sharply with the reddish tones that surround them. The sphere, almost always present in my paintings as a symbol of perfection, highlights the surreal atmosphere of the landscape.

The nearly photographic presence of the Torre del Mangia, symbol of civic power, is not accidental. The setting of “Ecstasy”? Perhaps the Piazza del Campo, or an arena, a place of strong representations.